Orolingual bradykinin angioedema after tissue plasminogen activator in acute stroke – treatment with or without C1-esterase inhibitor

Bradykininem indukovaný angioedém po podání tkáňového aktivátoru plazminogenu u akutní cévní mozkové příhody – terapie s nebo bez inhibitoru C1 esterázy

Autoři deklarují, že v souvislosti s předmětem studie nemají žádné komerční zájmy.

Redakční rada potvrzuje, že rukopis práce splnil ICMJE kritéria pro publikace zasílané do biomedicínských časopisů.

Authors:

V. Špatenková 1; D. Šímová 2; V. Beneš Rd 3 3; J. Jedlička 1

Authors place of work:

Neurocenter, Neurointensive Care Unit, Regional Hospital Liberec, Czech Republic

1; Neurocenter, Department of Neurology, Regional Hospital Liberec, Czech Republic

2; Neurocenter, Department of Neurosurgery, Regional Hospital Liberec, Czech Republic

3

Published in the journal:

Cesk Slov Neurol N 2018; 81(4): 478-480

Category:

Dopisy redakci

doi:

https://doi.org/10.14735/amcsnn2018csnn.eu2

Summary

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

Dear Editor,

The aim of this report is to compare the treatment of a bradykinin-induced orolingual angioedema (BiA) after recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) administration in two ischemic stroke patients, and to show how C1-esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) reduces the risk of hypoxia from an obstruction in BiA.

Orolingual angioedema is a sudden complication, a rapid progression of swelling, which can cause acute upper obstruction of the airways with the risk of acute hypoxia. Angioedema can occur for a variety of reasons, one of which is rtPA used in acute ischemic stroke patients. The incidence of angioedema after alteplase administration in ischemic stroke varies, with 7.9% being the highest reported in a study by Hurford et al [1].

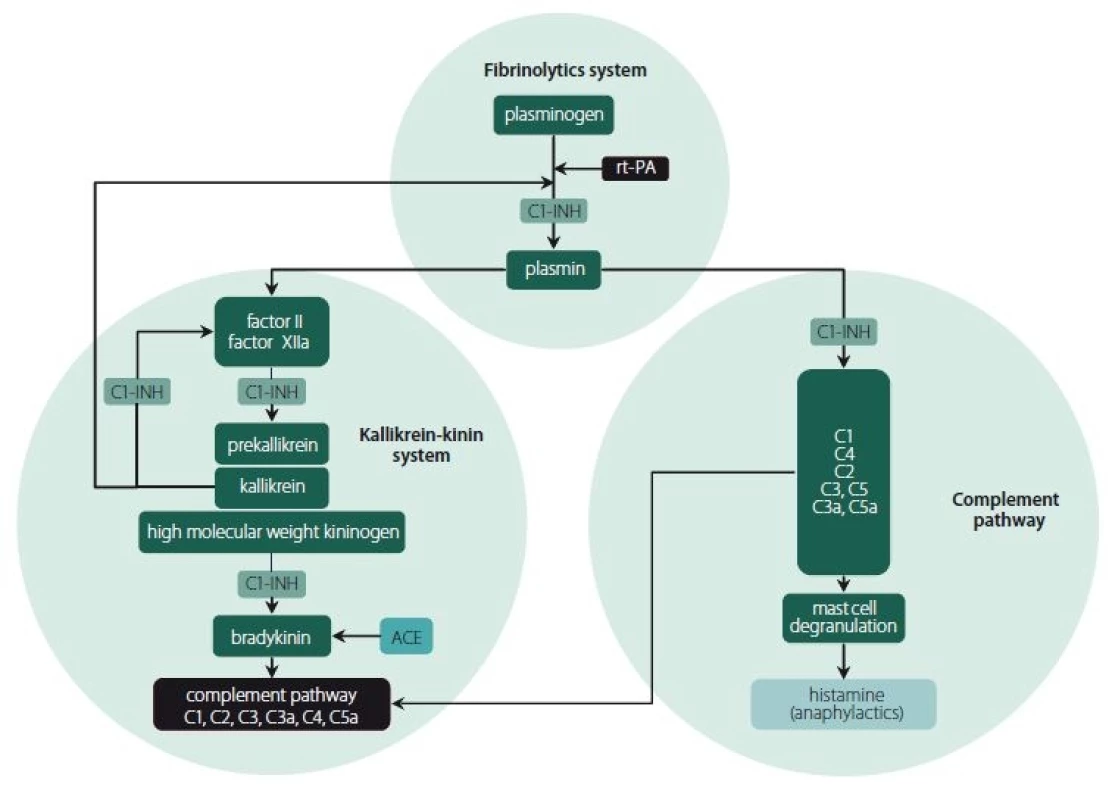

From a pathophysiological point of view, acute swelling of skin and subcutaneous tissue in angioedema occurs due to two different mechanisms (Fig. 1). Histamine-induced angioedema is usually allergy-related and can be treated with antihistamines, steroids and adrenalin administration. In contrast, BiA cannot be treated by the aforementioned drugs, since its development is based on different biochemical pathways. However, it can be treated with C1-INH. The BiA mechanism is based on bradykinin inducing vasodilatation and increased endothelial permeability after being released from high-molecular-weight kininogen by the action of plasma kallikrein. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors reduce bradykinin degradation and this explains why the risk of BiA development is increased among people taking ACE inhibitors [1– 3].

Acute hypoxia in acute ischemic stroke patients can worsen morbidity and mortality due to secondary brain damage. This complication therefore necessitates urgent treatment [4– 5]. In our neurocritical care unit during the period 2014– 2016, out of 489 ischemic stroke patients who received alteplase, angioedema occurred in two cases (0.4%), both of whom had BiA and had been using ACE inhibitors for arterial hypertension (AH). The edema in these patients did not respond to classic allergy therapy. The BiA of the first patient was resolved with an urgent video-assisted orotracheal intubation without C1-INH, while the second patient received C1-INH. This treatment was made available in our neurocritical care after the first dramatic situation.

The case reports are reported with written consent for publication.

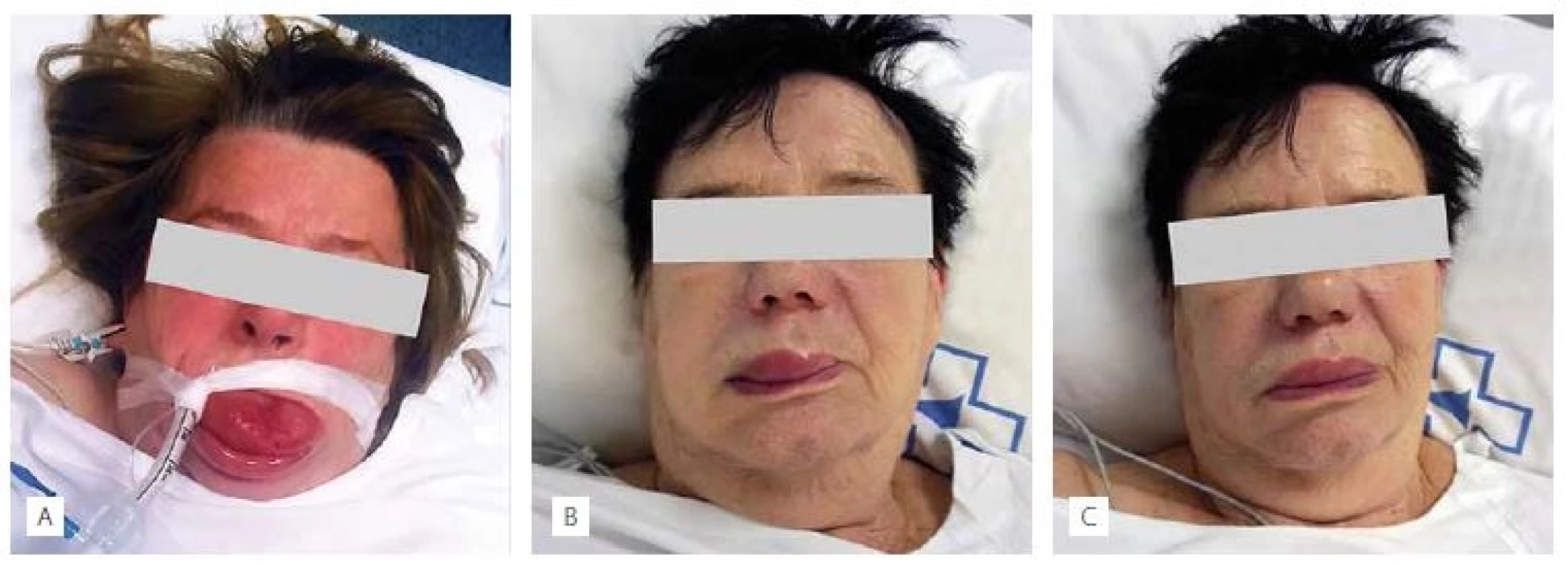

Patient 1 without C1-INH – a 78-year-oldwoman with a history of AH treated for 2 years with ACE inhibitors and no known allergies or BiA was admitted with severe aphasia and right-sided hemiparesis (3/ 5). Her admission National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was 13. Brain CT showed no apparent acute ischemic or hemorrhagic lesion, CT angiography showed no vessel occlusion so intravenous alteplase (75 mg) administration was started 150 min after the onset of symptoms. After 110 min, she suddenly developed severe orolingual and airway edema (Fig. 2A) which did not respond to adrenalin, steroids and antihistamines. Urgent video-assisted orotracheal intubation took place without any complications. The patient underwent 18 h of ventilation until edema resolution and was extubated without difficulties. Her neurological status partially improved (NIHSS 6) upon discharge.

Patient 2 with C1-INH – a 77-year-old woman with a history of AH treated for 3 years with ACE inhibitors and no known allergies or BiA was admitted with dysarthria and right-sided faciobrachial paresis (NIHSS 4). Brain CT showed no apparent ischemic or hemorrhagic lesion, CT angiography showed embolic material in the distal branch of the middle cerebral artery. Intravenous alteplase was started 180 min after the onset of symptoms (70 mg). Her neurological deficit progressed after 30 min (NIHSS 10). Alteplase administration was stopped. No changes could be detected on the urgent brain CT, so alteplase was restarted. After 70 min, the development of a right-sided upper lip, face and neck edema was noted (Fig. 2B). Rapid progression led to dyspnea and dysphagia. Administration of adrenalin, steroids and antihistamines was ineffective, so C1-INH (complement C1-esterase inhibitor Berinert®, 1500 international units) was applied. A very prompt resolution (30 min) of dysphagia and dyspnea was observed followed by gradual edema regression (Fig. 2C), and no orotracheal intubation was necessary. She experienced almost a full neurological recovery (NIHSS 1) upon discharge.

Serious allergic reactions (anaphylaxis) after thrombolytic therapy with rtPA have been observed during the treatment of acute ischemic stroke and Hurford even reported a 7.9% incidence of this complication after alteplase administration in ischemic stroke patients [1]. Upon onset of angioedema, we should bear in mind that angioedema can occur as a result of two different mechanisms, histamine or BiA as shown in Fig 1. These different mechanisms giving rise to angioedema require different treatments. Allergy-related angioedema can be treated by antihistamines, steroids and adrenalin administration. In contrast, BiA can be treated by C1-INH. This medication was also used in a minority of cases in the Hurford΄s study. Therefore, from a practical viewpoint, when the usual allergy treatments are ineffective, and in addition when the patient is using ACE inhibitors, we might consider BiA.

BiA is a sudden life-threatening complication due to the rapid progression of swelling causing acute obstruction of the airways. In order to prevent hypoxia, this complication must be resolved quickly by an expert physician who is skilled in performing video-assisted orotracheal intubation to avoid the last possible solution of a coniopuncture. Our first case report shows that although the patient was successfully intubated, without complications or hypoxia, we felt the need to pay attention to this issue and to keep C1-INH available for acute use in our neurocritical care unit. We were therefore able to effectively administer it to our second presented patient with BiA, who did not need intubation.

Even though our neurocritical care unit has a much lower incidence of orolingual angioedema than in the literature, we wanted to draw attention to this serious complication after alteplase treatment in acute stroke patients in neurocritical care. The question remains why our incidence of angioedema is so low in comparison with the Hurford΄s study, but in any case, orolingual angioedema is a risk factor for acute hypoxia, since it can be a fatal complication and therefore necessitates urgent treatment. When the usual anti-allergic measures are ineffective, and in addition the patient is using ACE inhibitors, BiA should be suspected and C1-INH can be considered for treatment of angioedema in order to avoid urgent endotracheal intubation or emergency cricothyroidotomy.

Accepted for review: 15. 10. 2017

Accepted for print: 5. 3. 2018

MUDr. Věra Špatenková, Ph.D.

Neurocenter, Neurointensive Care Unit

Regional Hospital Liberec

Husova 10

46063 Liberec

Czech Republic

e-mail: vera.spatenkova@nemlib.cz

Štítky

Dětská neurologie Neurochirurgie NeurologieČlánek vyšel v časopise

Česká a slovenská neurologie a neurochirurgie

2018 Číslo 4

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle

- Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy in carotid endarterectomies

- Imaging of peripheral nerves using diffusion tensor imaging and MR tractography

- Bilateral abducens nerve palsy after head and cervical spinal injury

- Late-onset Huntington’s disease – an overlooked diagnosis